There are many things I know very little about. Among those are the history of indigenous Australians and the history of indigenous Australian art. But it is also true that I know a little more about both than I did when I woke up this morning. That’s because Edie and I went to the National Gallery to see the exhibit titled The Star We Do Not See, an exhibit of about 200 works of indigenois Australian art from the National Gallery of Art of Victoria in Melbourne. It will be at the National Gallery until early March, when it travels on.

After it opened a few weeks ago, Washington Post art critic Sebastian Smee wrote a highly critical review of the exhibit, saying it contained some masterpieces, to be sure, but largely contained mediocrities, and that the National Gallery should not have brought in a prepackaged show from one museum, but hired a curator to search out only masterpieces and tell a more coherent story. He also said the exhibit is too inclusive, wanting to exhibit works by artists around the continent, sacrificing quality to do so.

Now Smee is a bit more qualified than I am to review this exhibit. For one thing, he is an artist and art critic. For another, he is Australian. But I won’t let that stop me.

You should see this exhibit. Why? Because the mediocre works are as good as the masterpieces. In fact, I have no idea which are which. I don’t think it is possible to tell.

A few things I did not know: Human history in Australia goes back 65,000 years. When the British came in the 1800s, there were indigenous communities all over the continen, with people speaking over 200 distinct languages. Each area had its own artistic traditions.

More: These communities suffered under the British. Poverty, disease, displacement.

More: the current trends in indigenous art only stems from the second half of the twentieth century, when the country began passing laws to protect it indigenous population. It was after this that the types of painting done on rocks, for example, were moved to more mobile surfaces. And, that modern paints could be used as well as natural dyes. And canvases became available, rathercthan only bark.

The art on display includes work on canvas and on bark, and includes three dimensional work. Here are some examples. These were some of my favorites. Whether they are masterpieces or mediocrities, I don’t know.

In addition, the names of the artists, their specific homelands, or what they are interpreting mean little to me. So I am going to post them with no explanations. If you see the show in person, or see what you can on line, you will undoubtedly learn more. Each piece, each artist, each locale is described.

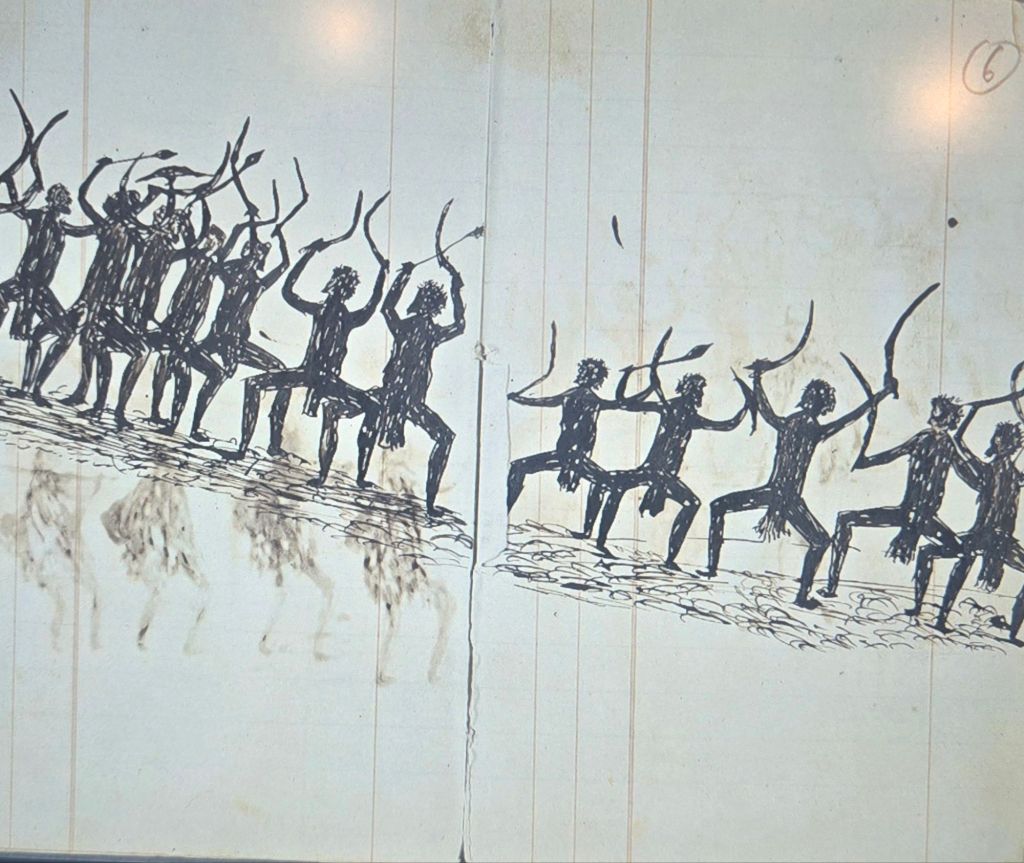

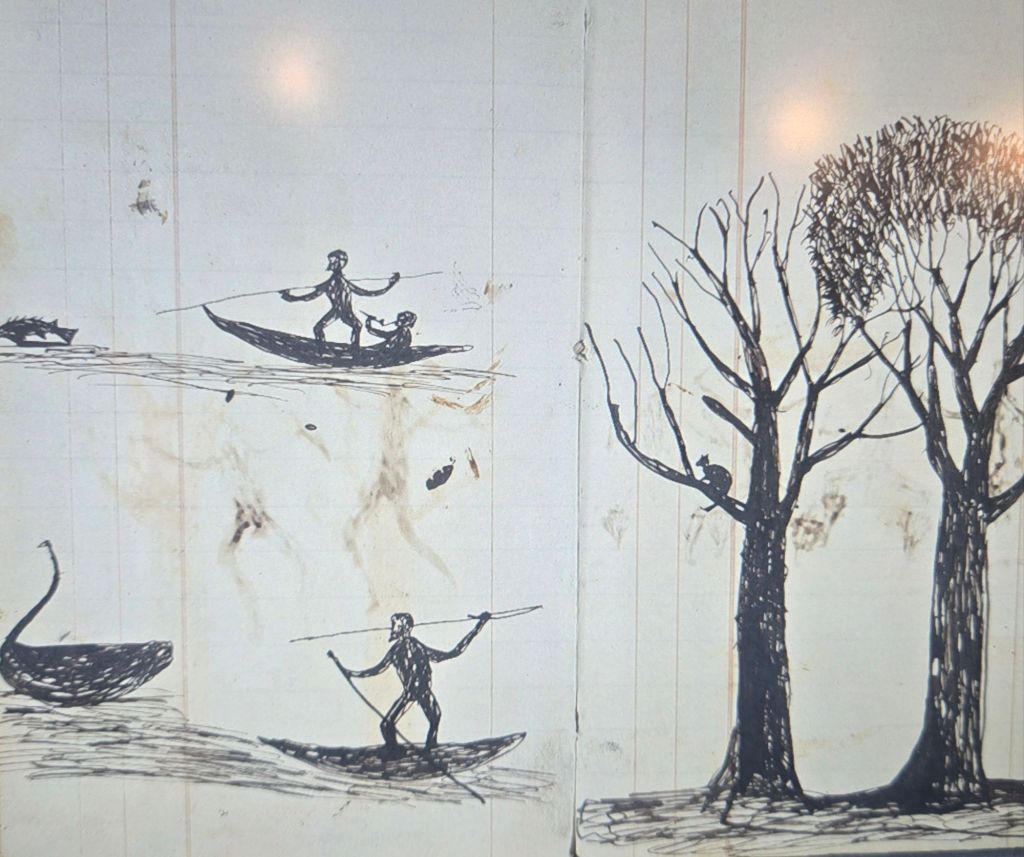

The oldest art in the show was in fact in a small book from 1875, put together by an indigenous artist for a British settler. Here are two pages from that book.

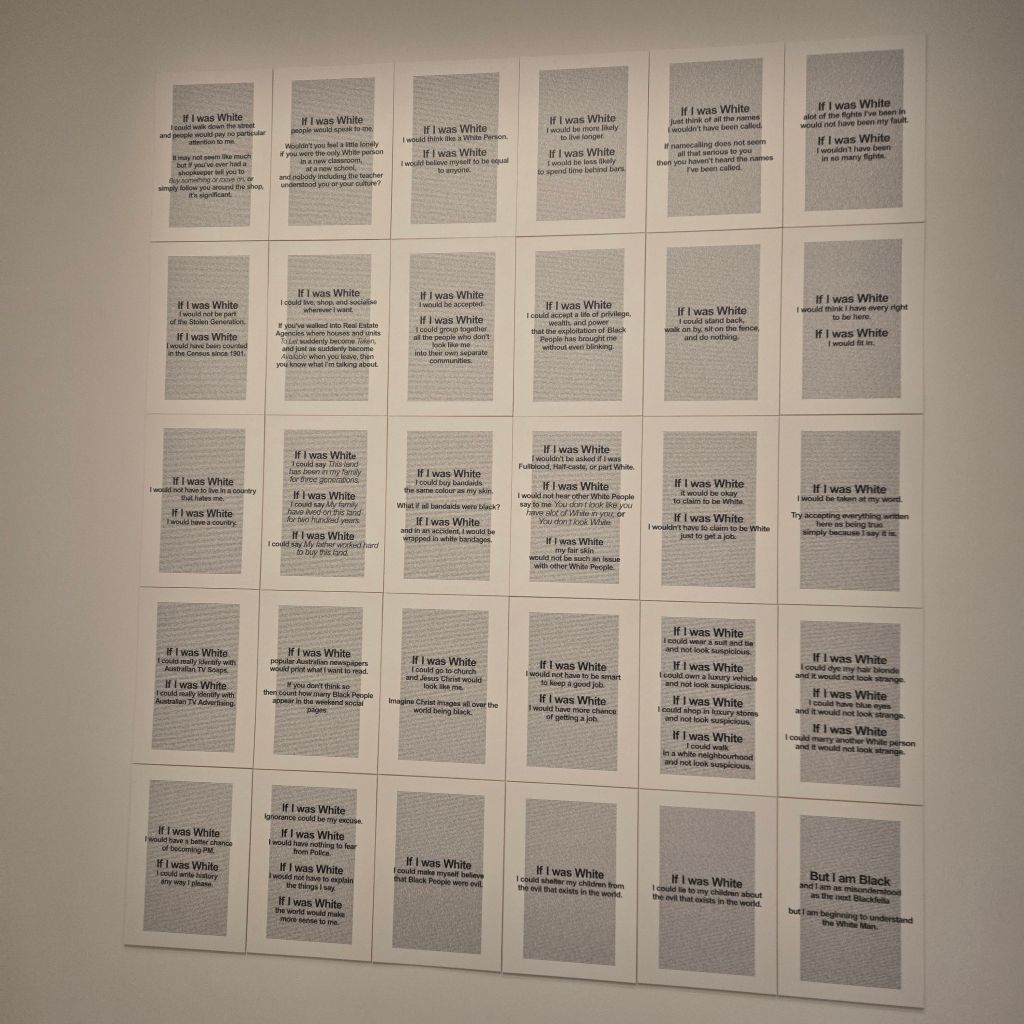

The last room of the exhibition shows more modern, less traditional works. I am only posting one, which actually contains only text. But each square is profound. I suggest you enlarge and read each of square.

And I repeat: Go see the show. Read his review and absorb what he says, but otherwise pay no attention to Sebastian Smee.

2 responses to “A Change of Pace, Mate.”

You’re right: All the artwork is fascinating, and I’d love to see it in person. I’m glad you did. Thanks for sharing some of it here.

That last image is universal and without each thought being (mostly) within the boxes could be reimagined as a poem.

LikeLike

agreed

LikeLike