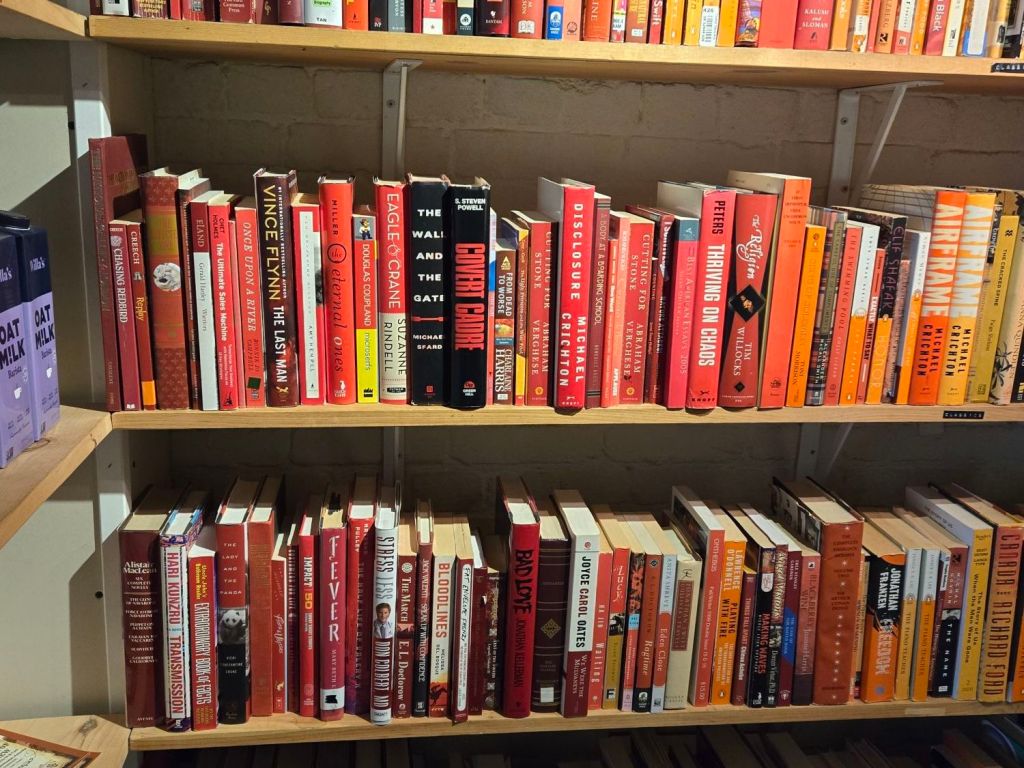

What did I read on my vacation? I actually finished one book, read another, and started (and stopped) a third.

The book that I completed was Robert Finnegan’s The Bandaged Nude, a 1950s mystery that I wrote about just before I left on the trip. The only thing I didn’t know then was who done it, and now that I know, I am not impressed. As one pondered all the possibilities, a new-ish character came in from left field and it turned out he was the one. That’s cheating.

The one I couldn’t finish, and I do thank friend T_____ A_____ for sending it to me was Michael Shaara’s Killer Angels, his 1975 book that won the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction that year. This is a book that everyone loves. But me. It’s the story of the Battle of Gettysburg, fictionalized not as to who won and who lost, but as to the emotions and conversations of the major participants. It’s just not a topic I care about (I care about what caused the Civil War, but not about how individual battles were won or lost), and I just didn’t have any interest the conversations during the run up to the war, especially as they were all made up. So, I went through a little more than 100 pages and decided that was more than enough. If you have read this book, I am sure you loved it. Everyone that I know did.

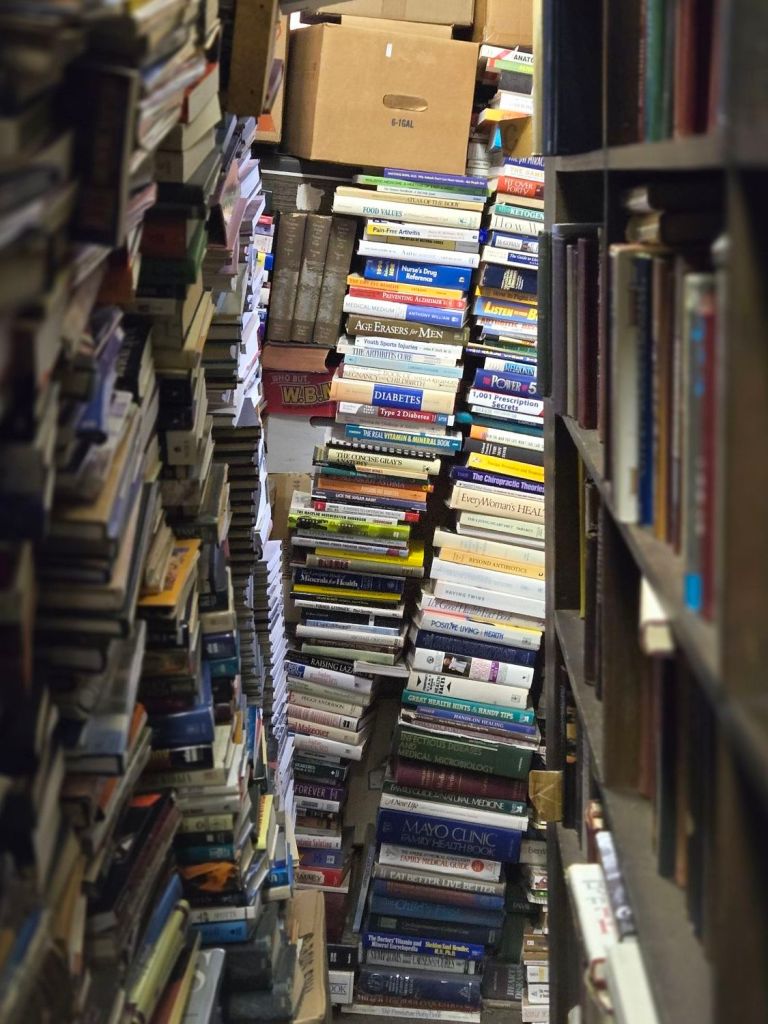

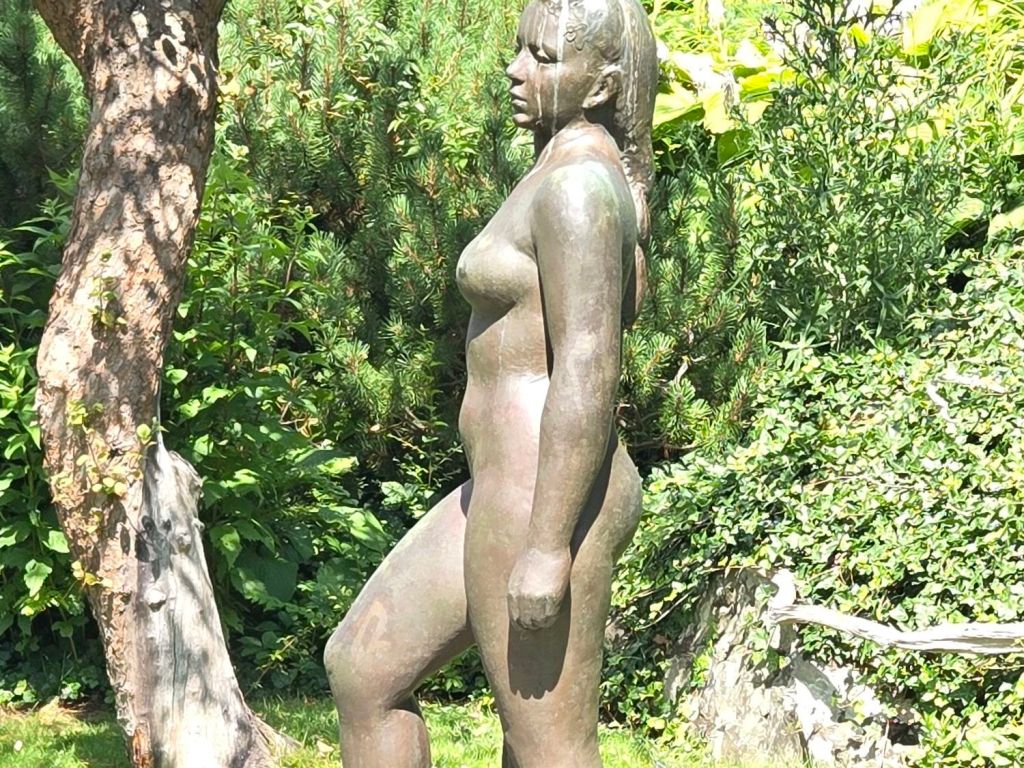

Having need, then, of something to occupy my time during our days hanging around friend N______ B_______ home in Kennebunkport (actually Goose Rocks Beach), I went to the local library’s basement book store (I had been there before) and bought a copy of Vladimir Nabokov’s Speak, Memory, much more my style.

You probably know Nabokov as the author of Lolita, and maybe more. You may know he was born in Russia (tsarist Russia), lived much of his life in the U.S., where he taught, wrote and chased butterflies. He is a clever writer, but not necessarily someone you want to have a drink with. Why is that? Not because he isn’t interesting, but because his world was so different from yours that I am not sure you’d have much to talk about.

His memoir (perhaps written for his wife? Unclear to me. And unimportant) came out when he was already a senior citizen, and it is comprised to a great extent of pieces he had written much earlier. Most of these pieces were written in Russian, translated (by him) into English, translated again from the English to the Russian (with emendations), and then translated back from the Russian to the English. He did all of this himself, which tells you (I am sure) something (but I don’t know what).

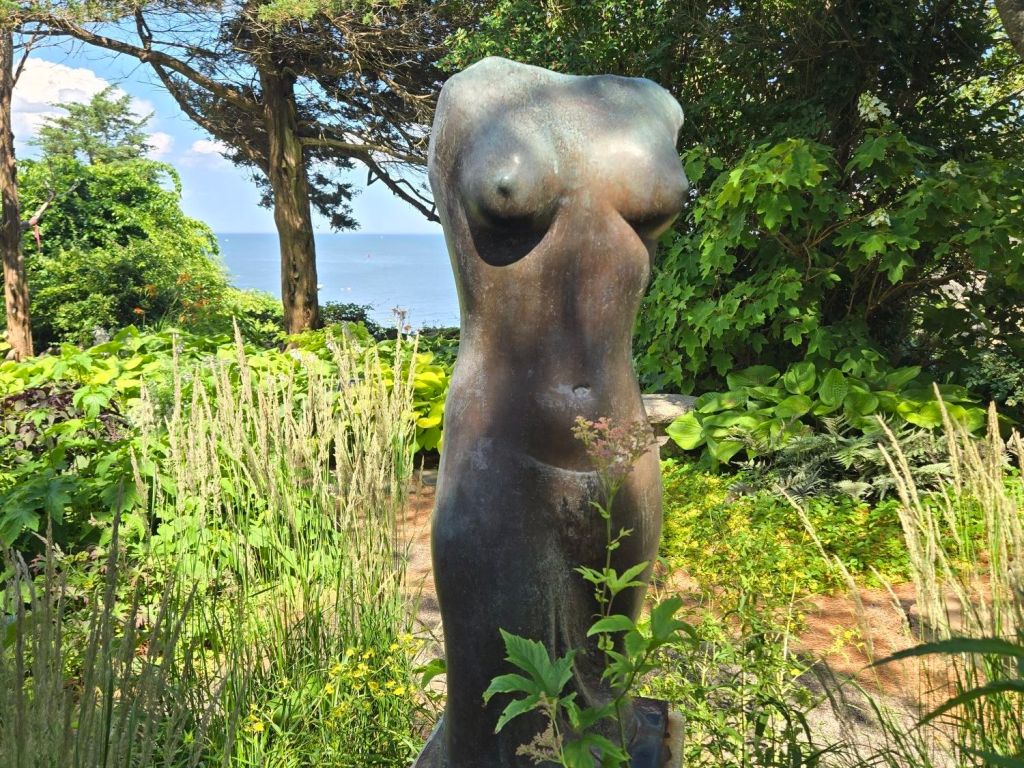

The book is only somewhat chronological. He divides it by subject matter, and some of the subject matter follows from earlier to later, but some does not. But there are chapters on his early years in Russia, his friends, his family, his schooling, winter, summer, butterflies, chess, exile, France, Berlin, Russian intelligentsia, more butterflies and more butterflies (and more chess – by the way the chess chapter is well beyond me).

Oh, and as to having a beer with him, you also learn that he doesn’t want to have a beer with you. After meeting Russian Nobelist Ivan Bunin for dinner in Paris, he writes: “I happen to have a morbid dislike for restaurants and cafes, especially Parisian ones – I detest crowds, harried waiters, Bohemians, vermouth concoctions, coffee, zakuski, floor shows and so forth. I like to eat and drink in a recumbent position (preferably on a couch) and in silence.” (I imagined him a couch potato, eating a couch potato.)

His life was clearly interesting. He was born in 1899 in Russia into a very, very, very, very rich and very, very, very important family of very, very noble people. Not only did his family have a large summer country estate (not to speak of a mansion in St. Petersburg), but each of his aunts and uncles had their own very large summer estates. At the Nabokov estate, they had approximately 50 servants, including cooks, cleaners, chauffeurs, gardeners, nursemaids, personal maids, valets and so forth.

He was an odd child, preferring his own company and the company of his butterfly net to anything else, so he was a loner much of the time, disappearing early in the mornings, and returning home in time for a midday meal. He got into trouble enough, and his intellectual ability might not have been apparent until later.

When the revolution came (his father, a leader of the Constitutional Democratic Party, had already been jailed by the tsar at one point), the Nabokovs left Russia. He father was killed by an assassin in 1922 in Switzerland where his mother remained, and Vladimir roamed around Europe for years until he came to America. Speak, Memory stops when he got to the United States, so we don’t hear about his years and accomplishments here.

Of course, when they left Russia, the uber-wealthy Nabokovs became the very poor Nabokovs, and Vladimir lived in Paris and Berlin, floating around intellectual emigre circles in various states of poverty, earning a little here and there from his writing.

And, oh yes, he did get to England where he studied at and took a degree from Cambridge. Another quote: “Not once in my three years of Cambridge – repeat not once – did I visit the University Library, or even bother to locate it. (I know its new place now.)”

In addition to being interested in most everything he writes about in the book, I am intrigued by the vocabulary he uses. He has an enormous vocabulary, and uses words you have never heard of in a casual way, as if they are the most common words in the world. And when he doesn’t have a word, what does he do? He just makes one up.

It’s 9:13 a.m. and I have a 10:00 a.m. meeting to go to in Rockville and I want to publish this post. Later today, I think I will put out a supplement that does nothing but show you some of the words he uses. I may even proof-read this one….something I have no time for right now.