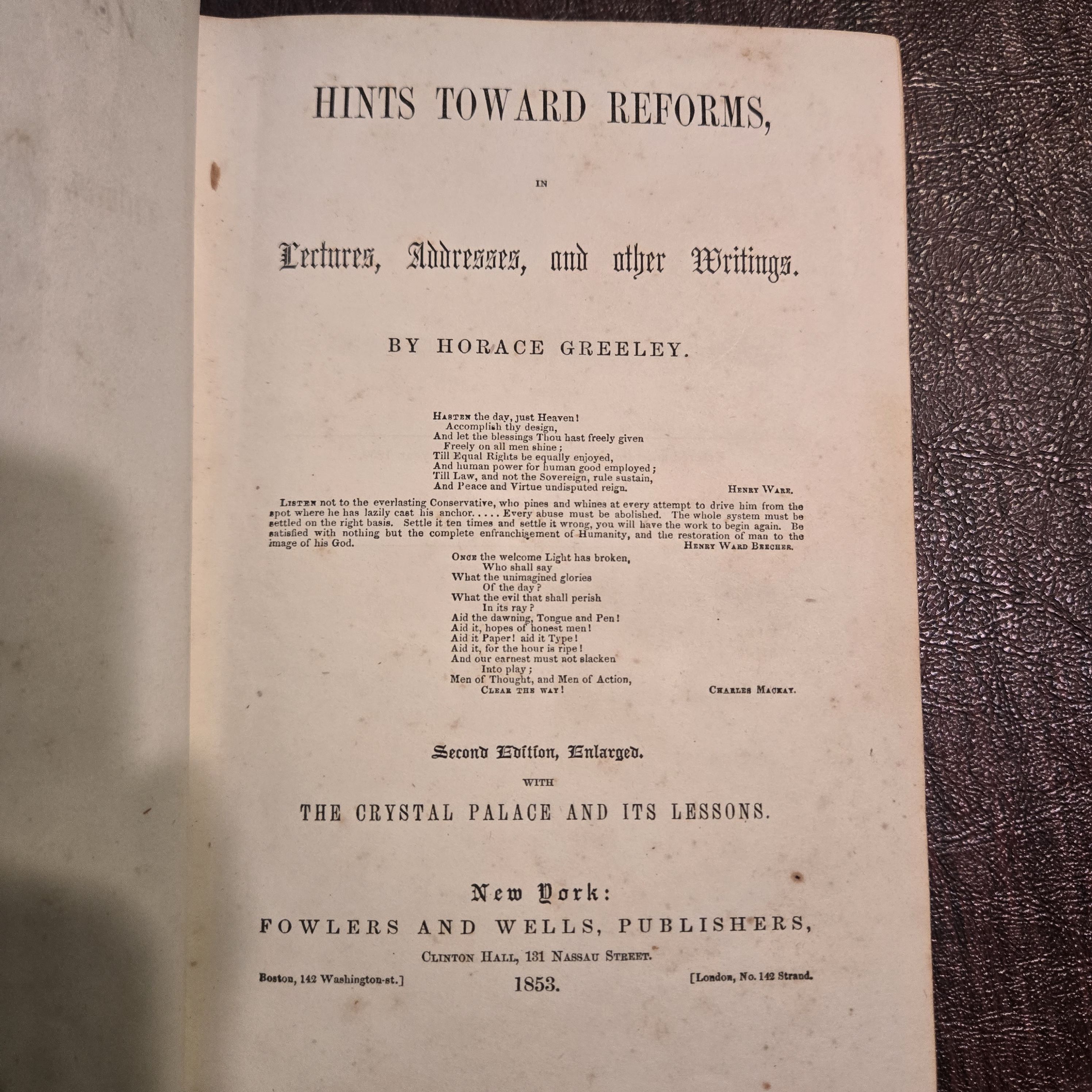

I returned today from Shabbat services not clear what my blog post would look like. I decided to go to another random bookshelf and report on what was there, but I did not get beyond the first book, Hints at Reforms by Horace Greeley. When I took it down, this post began to write itself. It is, in reality and substance, a bit “off the wall”.

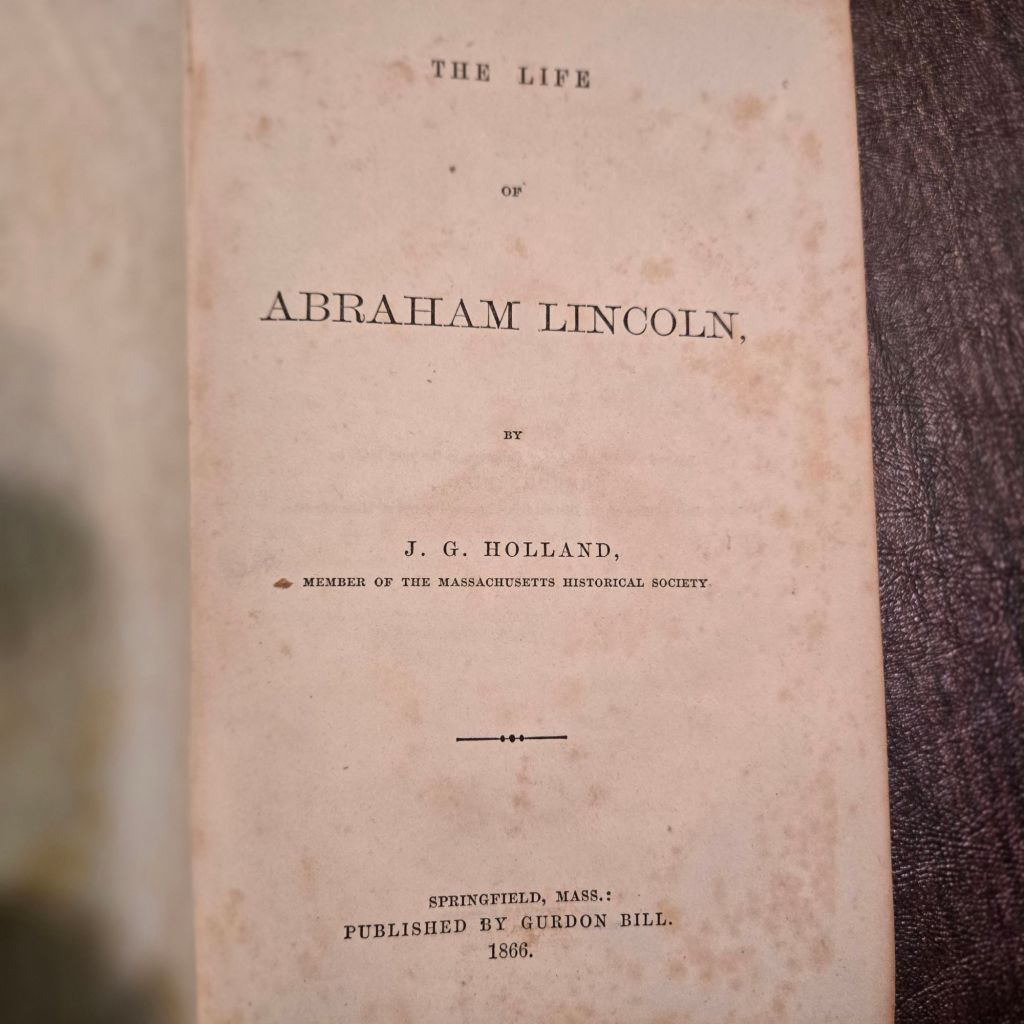

On April 14, 1865, Abraham Lincoln was shot and killed while sitting in the presidential booth at Ford’s Theater, on 10th Street NW, in Washington, DC. On the same night, Secretary of State William Seward (he, of Seward’s Folly) was attacked in his Washington house and very seriously wounded. The Civil War, which had been raging for five years and had resulted in the death of about 600,000 Americans from combat and disease, had just formally ended at Appomattox Courthouse (did you know that there were 2 t’s, 2p’s, 2 o’s, 2 a’s, but only one m in Appomattox?), but was still raging in parts of the country (or was it countries?). Washington was chaotic, to say the least. Who, in their right mind, would want to live here?

Certainly not Horace Greeley (1811-1872), editor of the New York Daily Tribune. Here is what he may have written in an editorial in the Tribune on July 13, 1865:

“Washington is not a place to live in. The rents are high, the food is bad, the dust is disgusting, and the morals are deplorable. Go West, young man, go West and grow up with the country.”

Makes sense in the context of post-assassination and post-Civil War Washington, right? But you note that I said above that Greeley “may” have said this in the July 13 edition of that newspaper. I said that because apparently no one can verify it. And the reason, from what I can see, that no one can verify is that it must not be there. If he said it there, everyone could look at what said and everyone would agree.

Obviously, I haven’t looked at this old newspaper myself, but it appears that geneoligist Mary Harrell-Sesniak has, because she says that she found much of this very quote not in July, but in the December 13, 1865 edition of the newspaper. Well, not the full quote, only the part about the depravity of Washington. She could find no evidence of Greeley ever telling young men to go West.

But if you search at encyclopedia.com, you will find that not only did Greeley give his instruction to young men in July 1865, but he not only did not claim to originate the phrase, but gave credit for the phrase to Terre Haute Express editor John Babsone Lane Soule, reprinting Soule’s use of the phrase in an 1851 article in Soule’s paper.

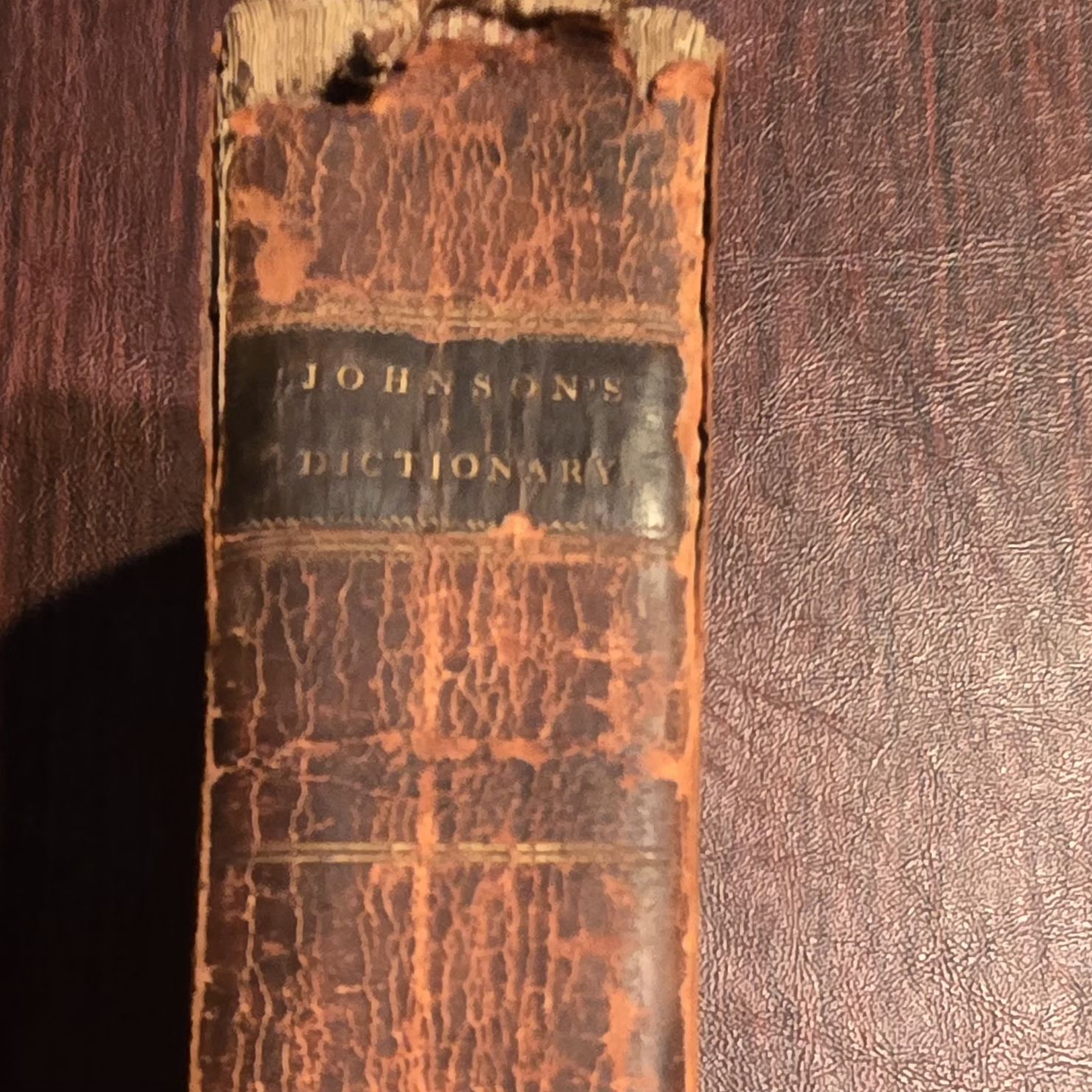

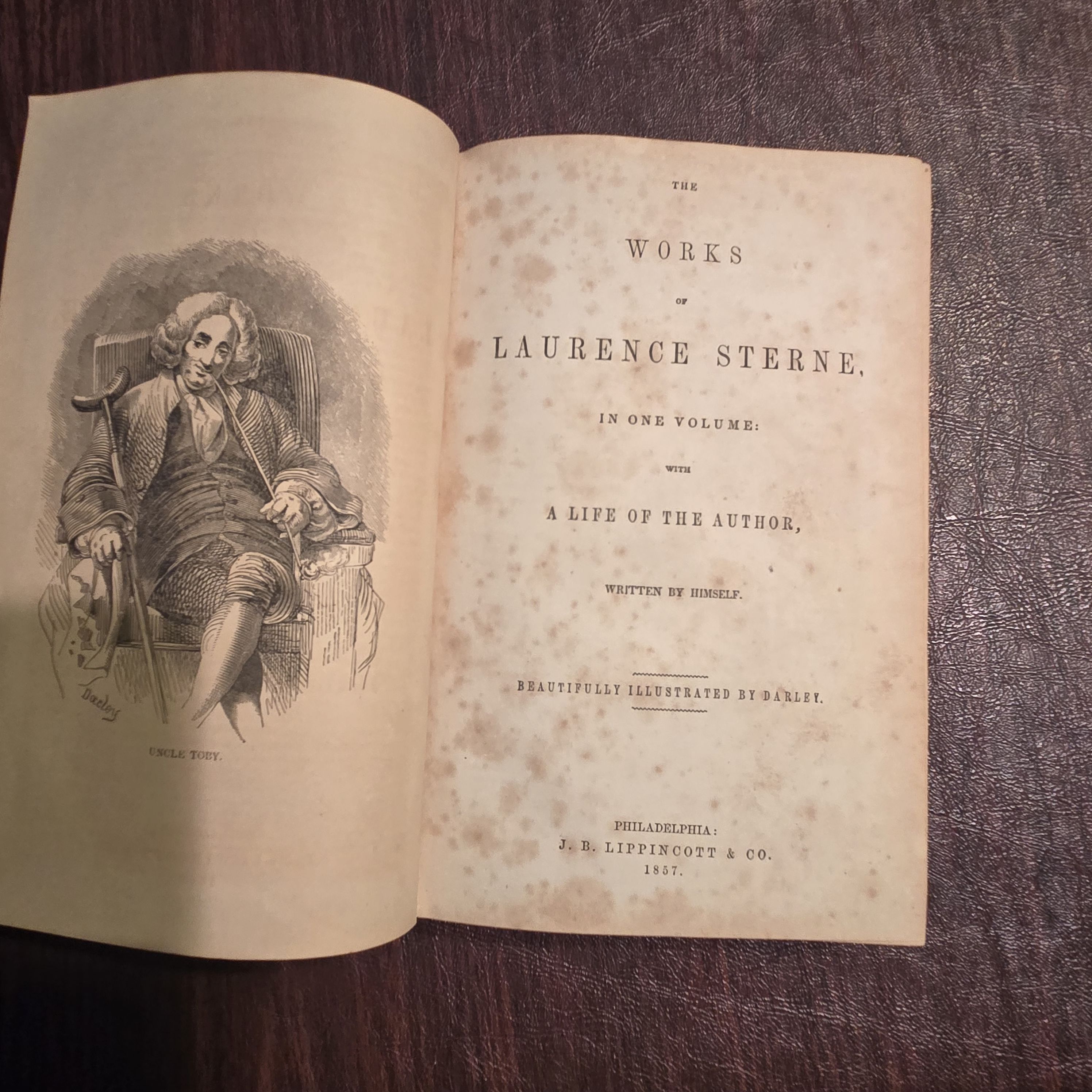

Further, according to Wikipedia, if you go to the Oxford Dictionary of Quotations, you will learn that the phrase was written by Greeley, but not published in the New York Daily Tribune at all, but used in Hints for Reforms, orginally published in 1850. This would precede the article by Soule.

Wikipedia tells me, however, that I shouldn’t waste my time looking for the quote in that book, because it isn’t there.

To make things even more complicated, Josiah Bushnell Grinnell (Iowa Congressman, abolitionist and a founder of Grinnell College), in his memoir, says that Greeley gave him this advice not in 1865, but rather in 1833, when he told Grinnell to “Go West, young man, go West. There is health in the country, and room away from our crowds of idlers and imbeciles.” Grinnell commented that such advice was like medicine that is easy to give, but harder to take.

I am not going to take this any further because it seems clear it would lead to more confusion, not less.

I will admit that I don’t know much about Greeley. He was born in New Hampshire, moved to New York, became a journalist, and established and edited the Tribune. He seems to have been quite an opinionated fellow, favoring western expansion (of course, he stayed in New York), as well as (says Wikipedia) socialism, vegetarianism, feminism, and temperance, along with pre-war abolitionism. He was an active Republican (one of the party founders) served a short time in Congress, thought Lincoln too slow on freeing the enslaved, and ran against Grant for president in 1872. He got three electoral votes, which was just as well, because he died before the votes were counted. Like so many others, he lies in Greenwood Cemetery in Brooklyn.

So where are we? Is this phrase original to Greeley? Did he first write it down? Who knows? After all, we really don’t know who wrote Shakespeare, do we?

And as to Hints at Reforms, sitting right here next to me…..is there something in it that would help us get on with our lives? If not, why did he even bother to write it? I guess I should open it up and see.

What did you do on your Shabbat afternoon?