“Did he believe all that he said? The question is inapplicable to this sort of personality. Subjectively, ____________ was, in my opinion, entirely sincere even in his self-contradictions. For his is a humorless mind that simply excludes the need for consistency that might distress more intellectual types. To an actor, the truth of anything lies in its effect; if it makes the right impression, it is true.”

This sounds like it was written in 2024 to talk about Donald Trump, doesn’t it? In fact, it was written in the 1930s, to describe Adolph Hitler.

Don’t worry – I am not saying that Donald Trump is a reincarnation of Hitler. But I am saying that there are certain personalities who can gather millions of followers who do share certain traits, and this refers to one trait clearly shared by the two of them.

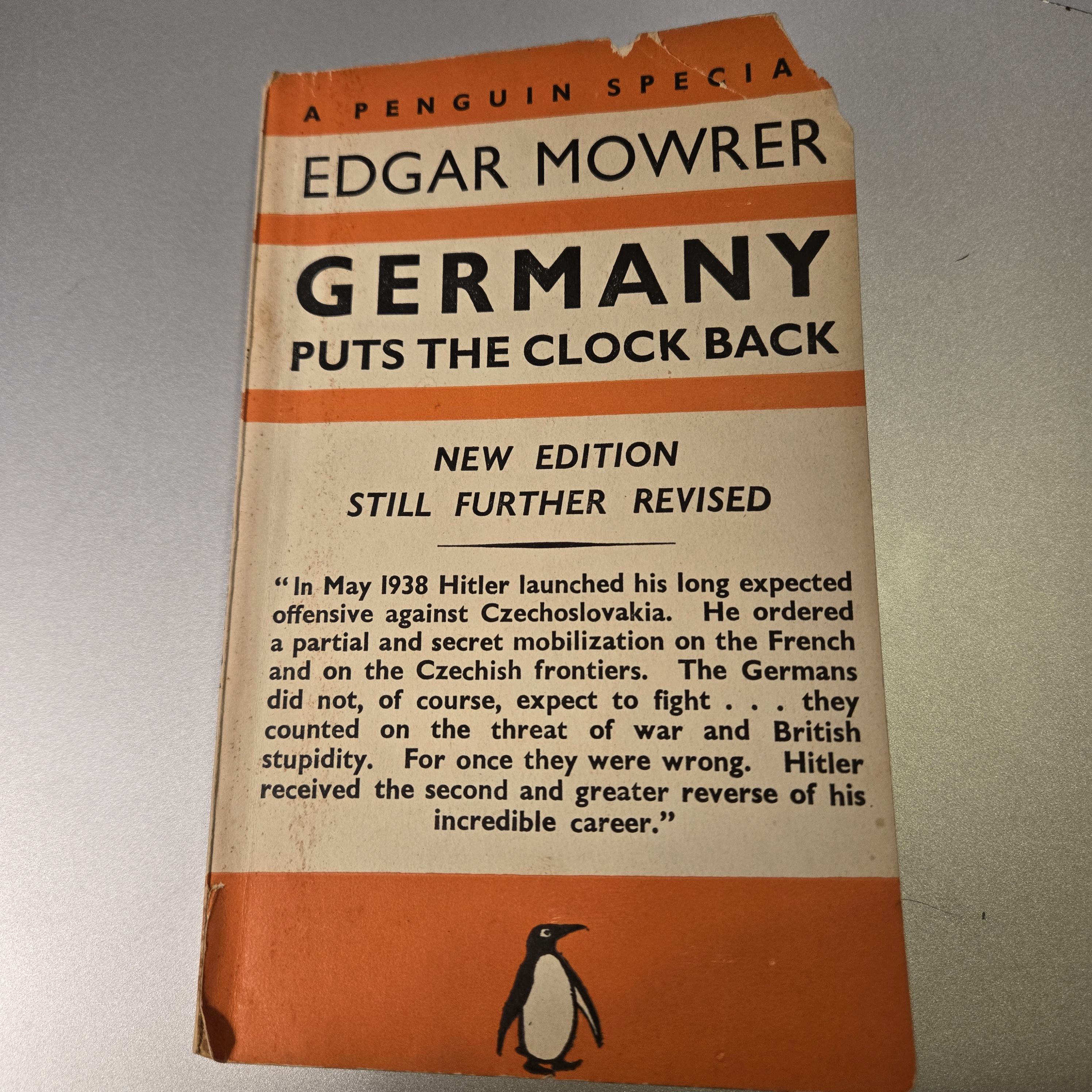

The quote comes from Edgar Mowrer, an American journalist, who published a book in 1933, with 1937 and 1938 revisions, called Germany Puts the Clock Back. We still remember Kamala Harris’ slogan “We Won’t Go Back”, right? It’s another similarity. It looks like we have.

I just finished reading this fascinating book, which was apparently a best seller when first published. It is primarily about Germany after World War I, the time of the Weimar Republic. It continues through Hitler becoming dictator of Germany in 1934, but ends prior to Kristallnacht in November, 1938 and the start of World War II in September 1939. Mowrer, obviously aware of the difficult position of the Jews in Germany when he wrote the book, had no clue about the eventual fate of the Jews not only in Germany, but throughout most of Europe, that was to come. As to World War II itself, he had his suspicions, but attempts were still being made to forestall armed conflict even at his final revision of the book.

So the book is not about World War II or the Holocaust, but about what happened between the time Germany admitted defeat in November of 1918, and the time that he finished his writing and revising, probably in 1938. We know the general story. Germany admitted it was at fault, it accepted a very onerous treaty developed by the winning powers at Versailles, it adopted a democratic constitution, and for 13 years, until the Nazi takeover in 1934, it became a very different country than it had been before World War I.

Germany in the 1920s and the United States a hundred years later are, of course, very different places, and can’t be compared to each other in any comprehensive way. But there are facets of Germany in the 1920s that may be similar enough to facets of today’s United States that they deserve examination.

Let’s look at some of the features of Weimar Germany, and see what we can glean from them that might be applicable to us today.

According to Mowrer (and I don’t know), the Weimar constitution was the most democratic and liberal constitution ever developed, but it was adopted by a country with no democratic traditions, and even at the beginning of Weimar, was supported by a minority “elite” of the population – well education, Western oriented, cosmopolitan. Most Germans then were not well educated, were certainly not Western oriented, and were very, very provincial. So there was a major gap between the government and the population.

At the beginning, this might not have mattered a lot. After the destruction of the first World War, the Germans appreciated time to rebuild, and the new government, supported many of Germany’s industrialists at the beginning, seemed to be succeeding, with full employment and a return to prosperity. This did not last, however, and soon the country was torn by extraordinary inflation and then massive unemployment. When the economy is failing for the majority of inhabitants, and the government seems far removed and controlled by people very different from the average man on the street or man on the farm, trouble cannot be far away.

At the same time, during the 1920s, there was a remarkable cultural revolution going on in Germany. Whoops. Let me restate this. There was a remarkable cultural revolution going on in Berlin. Avant garde art, atonal music, wild theater and dance, a sexual revolution, nudity on stage. You can imagine. All of this was very different from anything that Germany had ever experienced before. And, as visible as it was, these cultural phenomena did not run very deep at all throughout most of the country.

Germany had no experience of democracy, and most Germans distrusted democracy, did not see it bringing any improvements to their lives, and saw it run by people very different from true Germans. This is where the Jewish issue comes in. The Jews in Germany had been relatively free for a century or so, but not completely. Before World War I, there were always areas in government and levels in the military where they were not permitted to join. But under Weimar, the Jews were completely equal to any other residents of Germany, and they took advantage of it, becoming leaders in the government, and leaders of all of the cultural changes. An easy target, to be sure.

At the same time, even every government official was not a supporter of the Weimar regime. There was no equivalent of a de-Nazification program in Weimar Germany. Members of the pre-war regime were not cleared out of government. Many were allowed to keep, or to regain, their own positions. This was true particularly in the judiciary, where each jurist had, both before and after the war, lifetime appointments. The judges during Weimar Germany were by and large the same judges who presided during pre-war Germany, and according to Mowrer, their decisions evidenced that anti-Republican bias.

And finally, of course, there was the Versailles treaty itself, which put enormous financial burdens on Germany, prohibited the country from providing for its own self-defense (much less potential offense), and caused bitter resentment.

Enter the Nazis. They stood up for the little man, the working class man. At least that is what they said, although Mowrer points out this was strategy, not fact, and that in fact Nazi Germany was very elitist (as pre-war Germany had always been), and the working man was eventually completely forgotten. The Nazis stood up for the German people, the Volk. They showed that the Germans were Aryans and the Aryans were a special and advanced race, much more advanced than anyone else, especially than the Jews and the Blacks. They could blame every thing that was bad on the Jews, and their collaborators in the government. They could envision all the European Germanic people (the Austrians, and those in the Polish corridor and in Czechoslovakia, for example) joining together and establishing a super state. They would end inflation, they would end unemployment, they would end these dangerous cultural changes and revert to historic Germanic themes. They would rid the country of outside influences, including the dangerous notion that democracy was a desirable form of government.

And they would do this under the leadership, the absolute leadership, of Adolph Hitler, a man who could say anything and be believed, and whose oratory was mesmerizing to the masses. They would (and did) follow him anywhere.

Clearly, the United States today is not Weimar Germany. And, in extraordinarily important ways, Donald Trump is not Adolph Hitler. But some of the points raised by Edgar Mowrer in the 1930s do resonate today.

Kamala Harris might have thought she had a winning slogan in “We won’t go back!”, but she was wrong. For a great many Americans in 2024, as probably the majority of Germans in 1924, going back is just what they wanted to do.

The German desire to go back led to their own eventual misery, another World War, and the Holocaust. Out of all this, 100 years after Weimar, came a democratic Germany, western oriented, with an active Jewish population, and cosmopolitan. The old hierarchical, provincial, arrogant Germany appears to be no more. That requires another book. Probably been written a hundred times. Probably more.