I am going to try to do the Trump weave today, melding three distinct topics that seem to have nothing to do with each other into an intricate pattern that will appear seamless. My expectation is that I will fail. But who’s counting?

Today is Thanksgiving (you probably know that, at least if you are in this country), and my initial question is to whom is one expected to be giving thanks? Thanksgiving is, in most people’s mind, the ultimate secular national holiday, and certainly it is to the extent that it isn’t typically marked by religious services or rituals. But you can’t give thanks without directing your thanks somewhere, so it isn’t surprising when you look at Abraham Lincoln’s proclamation of 1863 creating the national holiday used words such as “[we]…..fervently implore the interposition of the Almighty Hand to heal the wounds of the nation and to restore it as soon as may be consistent with the Divine purposes to the full enjoyment of peace, tranquillity and Union.” As well as “to set apart and observe the last Thursday of November as a day of Thanksgiving and Praise to our benevolent Father who dwelleth in the Heavens.”

So, at least in its origins, the holiday was not fully secular, although maybe it was – to a great extent – not denominational. There is nothing specifically Christian in the wording, I don’t think. It is wording that religious Jews could endorse (after all, each Shabbat service includes a prayer for the country). And maybe Muslims, although I actually don’t know that, and there were virtually none in the country in 1863. Native Americans who had not been Christianized? That, too, I don’t know.

But, from what I can see, prior to Lincoln’s proclamation, there had been various types of “Thanksgiving” traditions that had developed, and most (if not all) of them were religious in origin.

So, how did Thanksgiving become a secular holiday? I read an interesting take on that, which said that secular Thanksgiving was a product of American education and American schooling, starting in the late 19th century, when the country was suddenly beset (that’s not the right word) with immigration on a scale never before imagined, and the task of American public schooling (which was for everyone then but the elitist of the elite) was to Americanize them. I don’t know if this is a good explanation, but it certainly is a thought provoking and interesting one, and one which I sorta like.

As an aside, it was in this educational secularization of Thanksgiving that the 1621 “harvest festival” of the Massachusetts Pilgrims and their neighboring Indian tribes became connected with the holiday. Until the late 19th century, when the American education curriculum was expanded to include Thanksgiving, it appears there was no connection between this historic event and Thanksgiving. The 1621 meal and meeting was probably held in early autumn, not in late November. And certainly Lincoln, in his rather lengthy proclamation (I should count words – was it longer than the Gettysburg address?) did not mention the Pilgrims.

That takes me to the second strand in my weave. Lincoln also did not refer directly to Blacks in his proclamation. That wasn’t a moral failure in and of itself, although in 1863, in the southern states and the four border states, slavery was still legal and practiced. For Blacks, therefore, was there any reason at that time to celebrate Thanksgiving? Who would they be thanking, and for what?

Last night, we watched the latest Denzel Washington Netflix August Wilson film, The Piano Lesson. I urge you all to watch it. It has received a 90% Rotten Tomatoes critics’ review score, although there has been some criticism for some of the choices made in adapting the stage play for the screen. I liked everything about the film, even when the mysterious “ghosts” of the play were made physically manifest on the screen. And the performances are extraordinary.

The story takes place in Pittsburgh in the 1930s, and the central, though nonspeaking, character is a piano dating from before the Civil War. A beautiful hand carved piano depicting family history, made by the grandfather (great grandfather?) of the current Charles family members. The piano was the property of the slave holding Sutters, but was stolen from the Sutter house by the carver’s son (who was afterward brutally murdered) and moved to Pittsburgh. And just recently, the last of the Sutters was murdered, found dead at the bottom of a well on his farm. The ghosts of both murdered men haunt the Charles family members.

The Charles family in the 1930s was no longer enslaved, but still haunted by slavery. Where was Thanksgiving in their consciousness? They might have believed in God, and this God may have their individual salvation at heart, but certainly not a national salvation. That, I am certain. What they would have done on the fourth Thursday of November, I don’t know.

So the concept of Thanksgiving, once you get beyond the food, Macy’s parade, the football games, and such, gets very complicated. Luckily, we don’t usually think about all of these things. Let’s keep it simple.

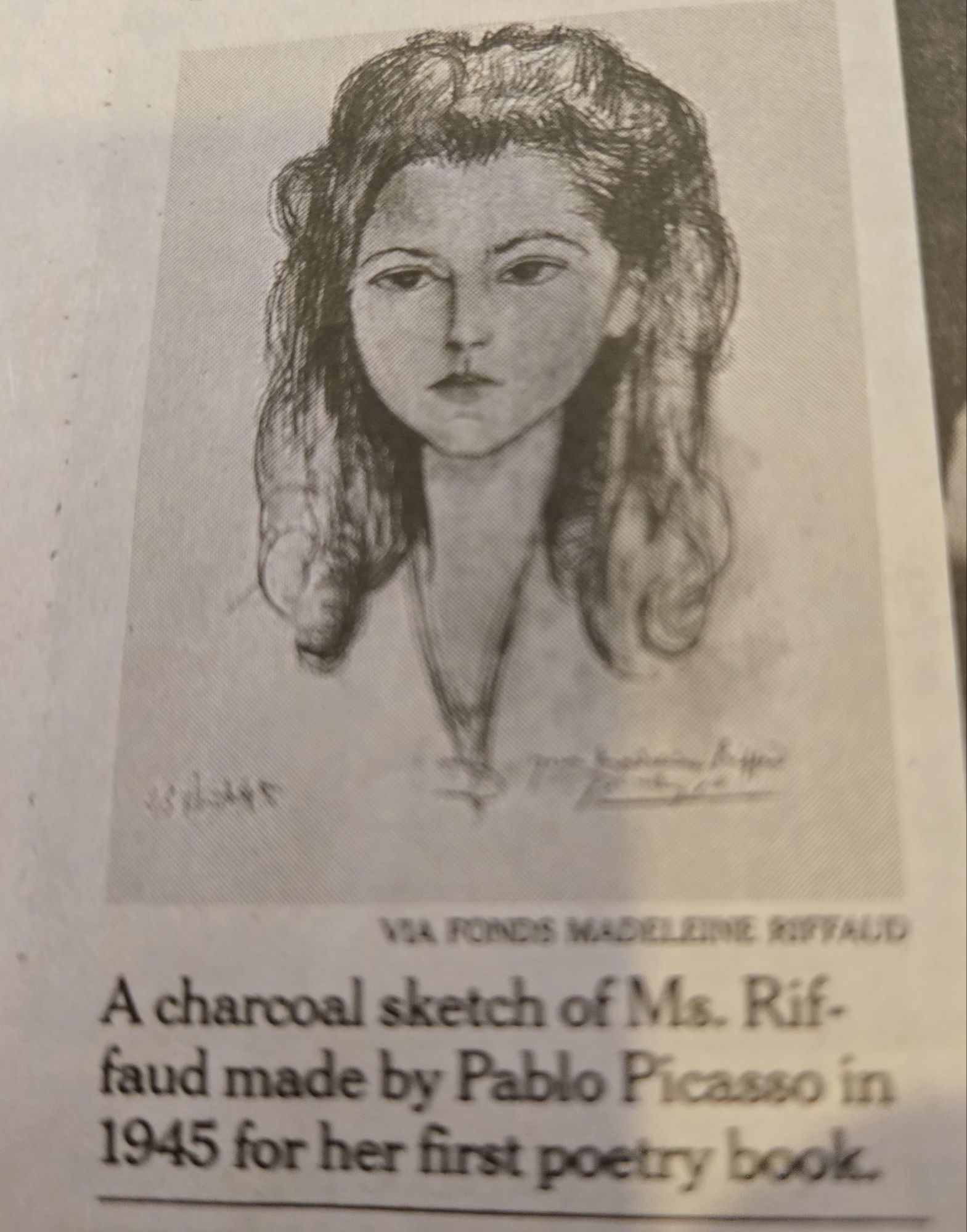

Thing number three? No time now. But look at yesterday’s New York Times obituary for 100 year old Madeline Riffaud. Can you weave her remarkable story into this post?