Last night, I had the privilege of introducing a speaker for the Haberman Institute for Jewish Studies, Professor Ori Z. Soltes of Georgetown University, whose presentation was titled: “The Changing Face of Jewish Art in the Modern and Contemporary World”. It was a truly wonderful presentation which not only discussed individual works of art, but also posed the obvious question of how a piece of work could be defined as Jewish.

For example, there are works of art portraying a Jewish subject, but by a non-Jewish artist. Conversely, there are works by Jewish artists which seem to portray totally non-Jewish subject matters. There are works of art by artists who were born Jewish, but were neither religious, nor whom necessarily identified with the Jewish community. There are works portraying “Jewish symbols”, which were not necessarily Jewish symbols. And so forth. And of course, Soltes did not give his own definition of Jewish art, but demonstrated the ambiguity in the term itself.

Within a day or two, the program should be available to be watched on the Haberman website: http://www.habermaninstitute.org. I suggest you look at it.

But as I listened to the presentation, my mind went to a question about Jewish art that Professor Soltes did not discuss (that isn’t a criticism) and to my recent visit to the Montgomery Museum of Fine Arts in (of course) Montgomery, Alabama. It is not a large museum, but it’s a museum with a lot of good art, and I did what I usually do at a museum. I stopped at works for art that seemed interesting to me, and I took a picture.

What I realized (maybe while even I was doing this) was that virtually all of the art that was the most interesting to me was, in fact, Jewish art. That is, it was either a work of art by a Jewish artist, or a work showing a Jewish subject. I do not know why this is. Perhaps, it is because things Jewish are the most interesting to me intellectually. Or perhaps it is because I am genetically drawn to such works. Or a combination. I am not sure.

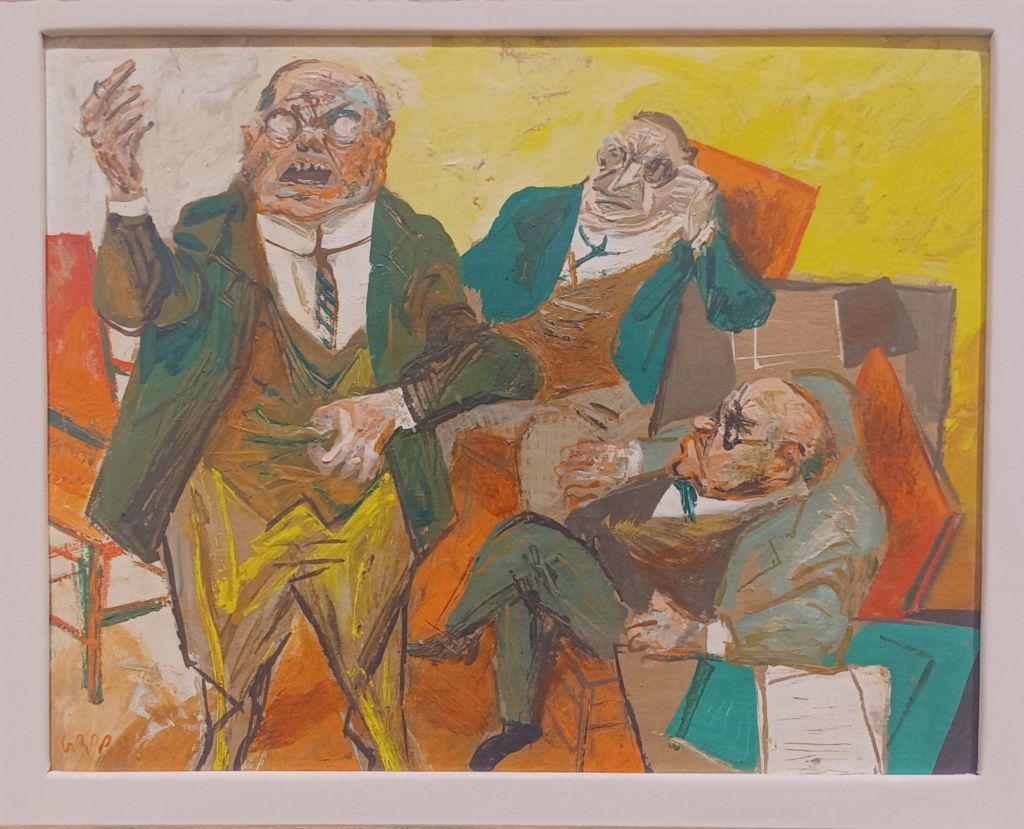

This first piece is called “The Caucus” and is by Jewish-American artist William Gropper (1897-1977). He was born to immigrant parents. His father was university educated and spoke eight languages, but couldn’t find appropriate employment. His aunt was killed in the Triangle fire. He became a radical. Not a Communist party member, but someone who spend time in the USSR and worked for radical publications. He was of course also strongly anti-Fascist.

The Caucus shows three men, presumably American, presumably quite self-important, in some sort of a meeting with one of them clearly expressing his opinion. You can assume that the other two would, as well. And you can conclude that whatever they are so engaged in is of no real importance.

There was a lot of this type of art done in the middle third of the twentieth century. I think they called it social justice art, or social realism. Is there something Jewish about this work? I don’t know. Is this a work that would only be done by a Jewish artist? Other than Gropper, I think of Ben Shahn, also Jewish. But German caricaturist George Grosz – he wasn’t Jewish.

Let’s move on.

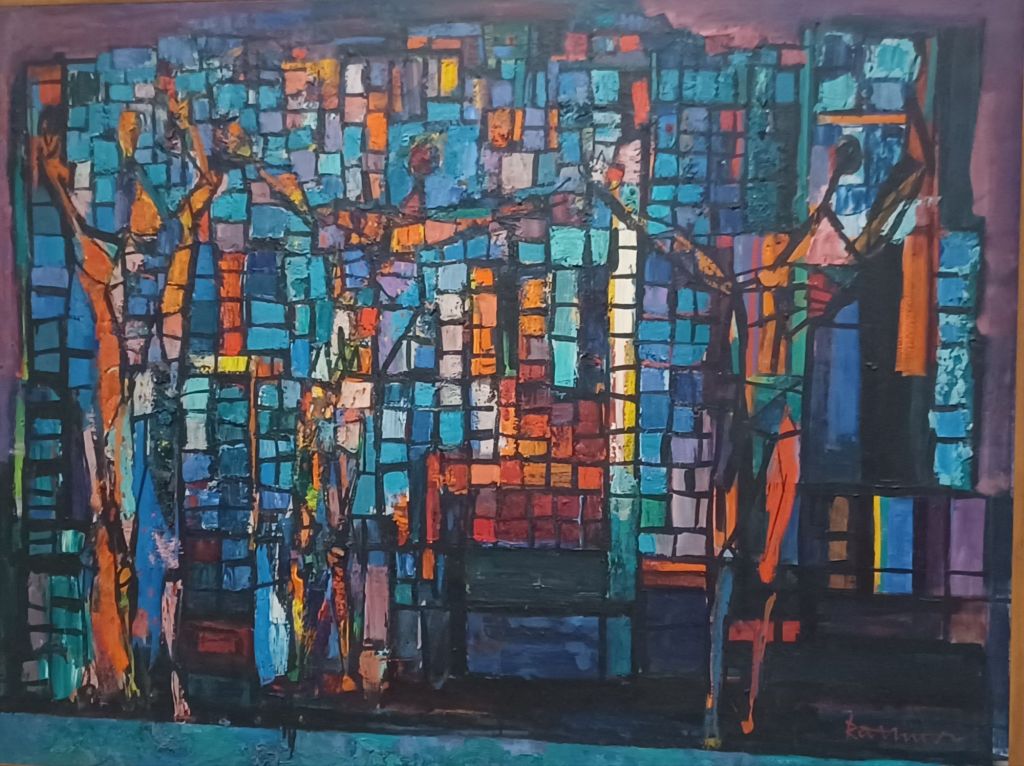

This one, called Composition With Three Figures, is by Abraham Rattner (1895-1978), like Gropper, American born of immigrant parents. As opposed to Gropper, I don’t know what Rattner’s politics were. He was not a caricaturist. He was more of an abstract artist, a master at the use of color. But many of his paintings, I now know, had a religious tinge about them. Whether that tinge was purposeful or accidental, I am not sure. I don’t think he tried to make religious paintings. But you can feel something of the spiritual in his work. Rattner’s work and Gropper’s are very different. Was there a commonality that attracted me to both?

Let’s do two more.

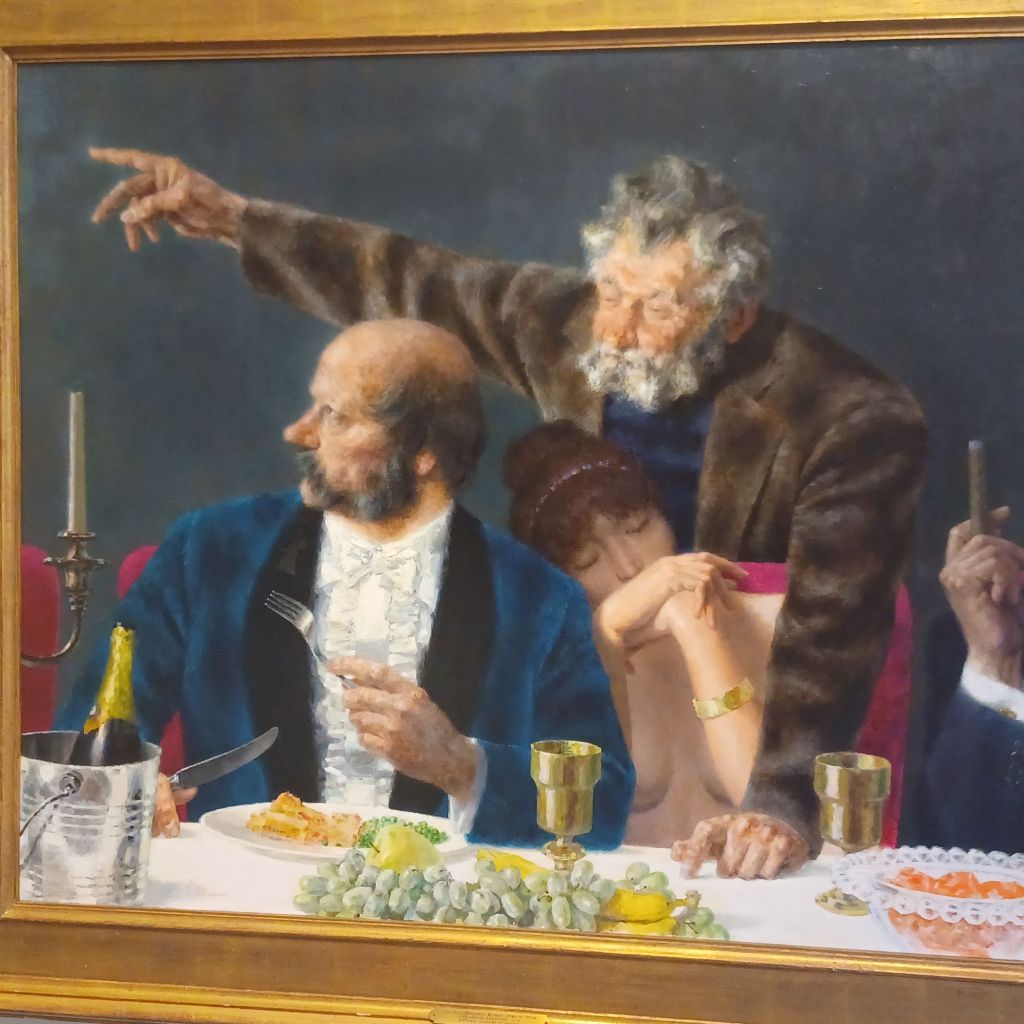

First, Daniel by Joseph Hirsch (1910-1981). Hirsch, whom I had neve heard of, apparently did a lot of religious painting……sort of. He took scenes from the Bible and updated them, placing them in modern backgrounds, clothing the subjects with contemporary dress. Here is apparently shows Daniel speaking to the king, Belshazzar, and entreating him to bring morality back into his government. An updating of a portion of the Daniel story, and a criticism of modern government – two in one.

In style, nothing could be more different than the other two. But again, I was attracted. And, oh, I guess I should make it clear that I was attracted to each of these paintings before I looked to see the names of the artists.

Finally, look at this one.

This is not by a Jewish artist. In fact is is by John Singer Sargent. But when I looked at the description, I saw it’s a portrait of Mrs. Louis E. Raphael (Henriette Goldschmidt). I don’t know how this painting wound up in Montgomery, but the Raphaels were, as I understand it, the second wealthiest Jewish banking family in London, behind only the Rothschilds.

Again, a very different type of art. But again, I really liked it. More than most Sargent portraits, I think, although I have never seen a Sargent that I haven’t liked. But there was something about Henriette Goldschmidt that spoke to me, I guess.

OK, to be honest, there were other pieces that attracted me that had nothing Jewish about them. Something by Reginald Marsh, by Edward Hopper, by William Christenberry, a Washington DC artist born in Alabama. But still.

One response to “Art on Art”

Good stuff!

LikeLike